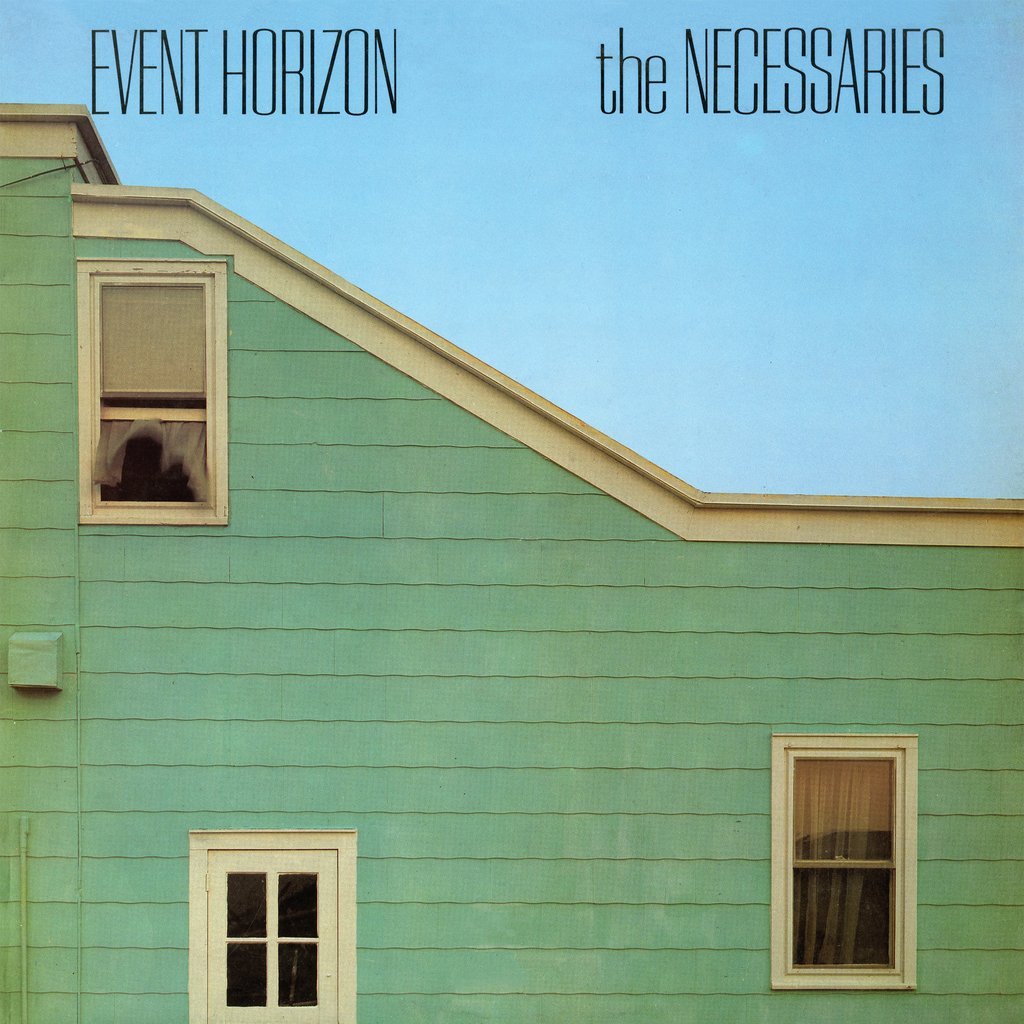

The Necessaries

Event Horizon

Original release: Sire Records 1982

Reissue: Be With Records 2017

Project Consultation and Liner Notes:

Michael IQ Jones

"The group has no niche, it doesn't fit in anywhere," explains Necessaries drummer Jesse Chamberlain in a 1980 Melody Maker interview. "We just state the facts about life in America, like The Clash did about England, but we're not so heavy about it." There's a fair amount of story to be told of this wonderful little American niche band, dear readers, but before we go any further, let's just get this out of the way immediately: contrary to popular revisionist mythology, the record that you are holding in your hands is not an Arthur Russell album, and The Necessaries weren't his band. All involved parties on this album had and would further take part in a number of other assorted Russell adventures both prior and subsequent to the recording and release of this album, but The Necessaries had taken shape a few years prior to Arthur's involvement, and featured among its ranks three monster talents who’d already tangled with a number of influential figures in the New York music and art scenes at the time before joining forces here. In telling this story, we end up also telling tales involving a great number of other characters, some quite infamous, others less so. One thing that is certain is that much of the information about the band’s history, with its metamorphosing lineups and lack of documented releases, has been wildly incorrect until now. We’ve got a lot of ground to cover here, but let’s pave this road and travel upon it beyond the Horizon. We’re taking a few twists and turns, maybe even a u-turn or two, but we’ve got clear skies along the way, I promise.

For now, let's start in 1979, when the band released their debut single. Even just a casual and cursory listen to "You Can Borrow My Car," produced by John Cale and released on his I.R.S. subsidiary imprint Spy Records, displays evidence of a vastly different (and more feral) animal than that which would go on to record Event Horizon. That 45, on which frontman Ed Tomney trades licks with fellow guitarist and singer Randy Gun while bassist Ernie Brooks and drummer Jesse Chamberlain pummel out a propulsive beat behind them, sounds like it was scraped off of the scummy bathroom floor of a CBGB's matinee gig. With its agitated spittle and winking, nudging lyrics playing more like a wry, parodic comment on the downtown punk scene than a sincere contribution to it, the song offers an all-too-brief glimpse of the sound that bookended the career of our unheralded heroes. Tomney, who wrote both of the single’s songs, had been a guitarist and vocalist in Harry Toledo & The Rockets, a lesser-known New York art-rock band who were an active part of the post-glam proto-punk scene centered around Max’s Kansas City from its revamp in 1975 until the club’s demise in ‘81. Toledo’s 1977 EP was Spy’s inaugural release, and features Tomney in rather prominent roles -- in addition to playing guitar throughout, he wrote three of the EP’s four songs, co-wrote the fourth, and assumes lead vocal duties on closer “John Glenn.”

The drummer on that Toledo EP was a young wunderkind named Jesse Chamberlain, who by the mid-70s had found himself in England enmeshed within the Art & Language collective, arguably the first creative group to recognize and identify the world's growing conceptual art movement, and whose membership at the time included a progressive free-thinking Texan named Mayo Thompson. Thompson had been the frontman for disbanded psychedelic counterculturalists The Red Crayola at the end of the 1960s, and when Art & Language purportedly dared Thompson to write music to whatever dense textual incongruities they could craft for him in the hopes of making a completely impersonal album of songs devoid of emotional signifiers, Chamberlain was recruited as Thompson's percussive foil. Together as a newly reconstituted Red Crayola, the duo would record Corrected Slogans with Art & Language in 1976 and the blistering, angular masterpiece Soldier Talk in 1979 with additional support from all of Pere Ubu. Chamberlain's work with Red Crayola is a dizzying frenzy of complex polyrhythmic shapes, his drumming often dexterously sculpting anchors and structure for Mayo's obtuse barbs as it simultaneously plays cat and mouse with Thompson's wiry guitar assault. "Mayo taught me a lot as far as 'Just play -- anything works in music, anything goes,'” said Chamberlain of his time in Red Crayola. "We had a great time, but as far as politics, I couldn't understand a lot of what he was talking about."

A desire for more contained and streamlined songwriting vessels eventually led Chamberlain back to New York, where a friend who had been making experimental electronic music with Tomney introduced the two. After an invitation from Chamberlain to visit the Tribeca studio that he shared with his sculptor father (more on that later), Tomney brought some instruments and, upon playing with the young drummer, experienced an immediate connection with his instincts, technique, and sheer power. He knew at that moment that he had to develop a project with him. “He was young, smart and a naturally gifted musician,” says Tomney. “He was a fast study, but knew exactly how and when to key in on my energy... there will never be another [drummer] like him.” Tomney eventually brought Chamberlain into Harry Toledo + The Rockets (that’s his drumming on the Spy EP), whose frontman had also brought in a guitarist and songwriter named Randy Gun (see where this is going?). After Tomney began moving in a different creative trajectory to that of the Rockets, he left the band and soon enough ended up taking both Gun and Chamberlain with him.

By this point, Ed had been gaining wisdom on the ins, outs, ups, and downs of the record industry from John Cale and publicist Jane Friedman of The Wartoke Concern, who managed Patti Smith and co-founded Spy Records with Cale. Cale’s 57th Street office in the Fisk Building, with its open-door policy, served as a Brill Building of sorts for Tomney and a number of players in the New York post-punk/new wave scene, which was undergoing the beginnings of its aesthetic metamorphosis away from the raw riffage of punk toward a wider embrace of more eclectic and experimental influences. Tomney, unsure of where to go next after leaving Toledo’s band, brought a solo tape of new songs to Cale in search of some constructive feedback. Cale, impressed by the tape, immediately called Tomney and enthusiastically suggested putting together a band as quickly as possible to start gigging in clubs and to build some momentum and interest for a record that Cale would in turn produce for Spy. During the pair’s lengthy conversation, Tomney threw around a handful of potential names for the new project; Cale’s favorite was The Necessaries, and with that, the group was birthed… now Ed just needed to find his new bandmates. The first players that immediately came to mind were Chamberlain and Gun; having enjoyed working with them in Harry Toledo’s band, he now had the perfect opportunity to use their talents in new contexts.

Gun, a mover and shaker around the New York rock community, had become friendly with Ernie Brooks, who had been spending a significant amount of time in New York after the dissolution of the Modern Lovers, a hard driving, hypnotic Massachusetts quartet fronted by the eccentric Jonathan Richman. With Tomney now needing a bassist, Randy had been the one to introduce him to Brooks, and while Tomney had been a Modern Lovers fan and definitely saw the appeal in working with the bassist, it was Brooks’s deft ability to lock in with Chamberlain’s tight but complex grooves that cemented his inauguration into the group. A Harvard-educated English-lit graduate who was also an able songwriter himself, Brooks had also formed a band in the mid-’70s with cellist and composer Arthur Russell (prior to either having joined The Necessaries), but we'll come back around to that too, I promise. (You should know by now that practically nothing involved with Arthur Russell is linear in nature, right?) After recording “You Can Borrow My Car” and “Runaway Child” with the group for Cale and Spy, Randy Gun left the band to pursue a solo career. He had first bonded with Brooks that night at CB’s over a shared love of the sort of tight, catchy pop structures that the Modern Lovers sought to pay homage to in their initial incarnation—bubblegum that had seemingly been chewed up and spit back out onto gravel—and he amicably parted ways with Tomney and co due to a desire to explore that pop route more intimately. He was replaced by renowned British guitarist Chris Spedding, a longtime, heavily in-demand session musician who had by that point played with the likes of Jack Bruce, Bryan Ferry, and Brian Eno, as well as with UK jazz heavyweights Mike Westbrook and Ian Carr. It was an extended contract as lead guitarist for American rockabilly revivalist Robert Gordon, though (replacing Link Wray, of all people!), that led Spedding to Tomney, Brooks, and Chamberlain.

Chris Spedding would sit with The Necessaries at their rehearsal studio on Vestry Street in Tribeca after becoming friendly with one another, introduced via their producer John Cale, whose own trio of Island Records albums heavily featured Spedding. When Spedding's aforementioned tenure with Robert Gordon had ended, Chamberlain suggested to Tomney that they approach Spedding about becoming a fully integrated member of The Necessaries. sharing songwriting, guitarist, and frontman duties with Tomney, and he agreed. Despite his cachet in the rock world at the time, Spedding had zero desire to be a solo artist or to assume control of The Necessaries. As Tomney and Spedding discovered that they shared sufficient tastes and a mutual admiration for one another’s material, they agreed upon a fully democratic approach in which each party brought their songs to the band, enabling Spedding to focus more energy on guitar work rather than bandleading, while Tomney could flex his muscles and build up his chops with one hell of a lead guitarist assisting. The quartet devised a plan in which they’d spend one year attempting to secure a record deal with a major label, helped in part by Chrissie Hynde choosing them as the opening act on The Pretenders’ first North American tour. A record contract proved a more difficult goal than expected, though, as Spedding’s fans were often confused and pissed off that he wasn’t completely steering the ship, while Necessaries fans were puzzled by the addition of a second frontman. While the band in turn did gain a larger following in the end thanks to their combined talents, a deal was not secured, and per their mutual agreement, they parted ways with Spedding. There's no recorded evidence of Spedding's tenure with the group that ever saw release, but his solo album I'm Not Like Everybody Else-- recorded shortly after his departure from The Necessaries, who somewhat ironically scored a deal with Sire Records soon after-- offers a partial glimpse into what his contributions to the band could have sounded like, as many of the album's songs featured in Necessaries setlists throughout 1980. While it should be noted that Spedding's "Depravitie," "Box Number," and "Counterfeit" do not feature Brooks, Tomney, or Chamberlain's talents (none of them, in fact, appear on Chris's album at all), the songs could all easily slide into a playlist among the cuts on Event Horizon, offering a subdued aesthetic hint at what was soon to come for our heroes, despite not featuring any of the frenzied interplay between Spedding and Tomney’s wildly different but equally powerful playing styles. Consider I'm Not Like Everybody Else a worthy footnote listen once you've devoured the songs here-- it's an inexpensive, relatively easy find in the used bins.

With Spedding out of the fold, the band continued for a short time as a trio, gigging and laying the groundwork for what was to be their debut album, until Brooks had the idea to recruit Arthur Russell as their new wild card. Brooks had been collaborating with Russell in a band called The Flying Hearts after the Modern Lovers fell apart, and was struck by the cellist’s “melodic flights” and unique approach to songcraft. Russell had first introduced himself to Brooks after catching a Lovers show in early 1975, and had stirred up controversy when he would go on to book the Massachusetts band (by this point a largely acoustic ensemble featuring a different lineup than that which had cut “Roadrunner”) later that year at The Kitchen, the contemporary art and performance space where Russell briefly served as musical director. While many in the NYC new music scene initially balked at the idea of incorporating rock music into the Kitchen's programming due to its frequent structural and aesthetic inflexibility, Brooks (along with a number of fellow Russell collaborators) saw a spark in Russell's bright but blurry ingenuity, and the two became close friends and frequent collaborators. A small handful of the recordings that Russell and Brooks made during this pre-Necessaries period can be heard on Arthur's posthumous Love Is Overtaking Me collection, and it's during that collection's second half that the DNA of Arthur's contributions to Event Horizon can be most vividly foreshadowed—rather than the droning, aquatic lullabies of his solo cello songs, the freeform rhythm clusters of his avant-dance platters, or his slow-motion instrumental movements for classical/art music ensembles, Overtaking’s songs sway upon a more overt country-pop axis, more closely obeying verse/chorus structures than anything released during his lifetime and allowing more breathing room in their arrangements than anything else to his name.

As evidenced by the Flying Hearts material, Arthur could go full pop if and when he wanted to, and he too had connections with Sire Records thanks to their having released his first dance single, Dinosaur's "Kiss Me Again," back in 1978. While Tomney was initially reluctant toward Brooks's requests to grant Russell's entry into the Necessaries roster—he'd first witnessed Russell's now-infamous unpredictability during the chaotic 1979 sessions for Dinosaur L's 24 -> 24 Music LP, which features Ed's guitar work—he and Chamberlain eventually acquiesced. What followed was certainly unlike anything else in Arthur's discography, a rare moment in which he subdues his eccentricities just enough to let others flex their muscle. After initially being courted by Warner Brothers, the band set up shop in Blank Tapes Studio with engineer Bob Blank at the helm to record what were meant to be demos, before being moved over to Sire to get signed. They continued to cut basic tracks with Blank for their debut, but due to both a miniscule recording budget and an upcoming tour, they were unable to get sufficient overdubs recorded, and put recording aside for the time being. While on the road in the American midwest, the band had discovered to their shock and dismay that Sire had issued those rough, rushed sessions as Big Sky-- without any input or approval by the band regarding mixing, mastering, etc. Big Sky shares six songs with Event Horizon, but save for the former's excellent opener "Back To You," there's not much that the band didn't manage to refine and polish more brightly by jettisoning those five remaining songs and returning to the studio with an additional recording budget to record new tracks and metamorphose the LP into what became this album. Instead of returning to Blank Tapes, the band chose to work with engineer Michael Ewing at his Sundragon Studios, and despite still being rushed for time by Sire, Ewing’s input and technical guidance made the best of what was essentially an unsatisfactory situation for the band. Big Sky ended up being a bit of a claustrophobic misnomer compared to the vivid open-road vistas of Event Horizon.

That's right: for a bunch of New Yorkers, the Necessaries wrote damn fine songs for road trips. These are songs for long stretches of open highway and endless fields as far as the eye can see, powered by the fluidity of a muscular rhythmic motor. It shouldn't really be much of a surprise, though; in "Roadrunner," Brooks's bass anchored one of the Modern Lovers' most enduring songs about driving around aimlessly while blasting the car radio, and the Necessaries' own debut single was a snotty, sarcastic, and borderline-questionable Killed By Death anthem about an automotively-challenged delinquent bumming the keys to a friend's ride in exchange for a date with his own sister. Add to this Jesse Chamberlain's father being none other than renowned Abstract Expressionist sculptor John Chamberlain, whose primary works were created with discarded and salvaged auto parts that had been welded and twisted into vibrant technicolor assemblages, and the band's conceptual love of the iconography of the road comes into view more explicitly. Event Horizon's subject matter is considerably more mature than that of "You Can Borrow My Car," proving that debut 45 to indeed be a bit of a novelty in more ways than one, but what's most surprising when listening to the album is just how well Tomney and Russell’s voices seem to both complement and juxtapose one another over the course of Event Horizon's runtime. Tomney's stark, clean, wiry guitars provide a focused contrast to Russell's tendency to obscure his songs into hazy, amorphous aural projections, while Arthur's trademark blur and fuzz adds incongruity and a touch of unsettled mystery to Ed's more muscular and aggressive offerings, like the stunning opener "Rage," whose tight, propulsive anxiety builds to a multi-tracked climax of distorted cello runs and mournful background cries by Russell as Tomney, Brooks, and Chamberlain motor the groove forward. The two balance one another almost perfectly, and the inclusion of two songs each by both Russell and Brooks on Event Horizon proved to be a brilliant move—the confident tenderness of their voices during their respective lead vocal turns provides sporadic pastel color, like pure pigment scattered across dusty, sun-bleached Americana.

Many of the album's best moments emerge during both literal and figurative harmonies between Ed, Arthur, and Ernie's voices, like on Brooks’s enduring single "Driving And Talking At The Same Time," whose dual vocal lines (that’s Brooks singing lead) intertwine as Arthur's noodly electric organ softly scribbles curlicues atop Tomney, Brooks, and Chamberlain's relaxed motorik groove. On the stuttering thump of Tomney’s "AEIOU," Ed and Arthur pull off some lovely light and shadow with their voices, as they recite the lyrics simultaneously in near identical styles before veering off into their own trademark tones; behind them, layers of Tomney’s guitars chime high atop the arrangement as Brooks’s bass percolates and Russell saws at his cello, thickening the low end into a deep growl. Brooks’s "Detroit Tonight" is the album’s beautiful slow jam, with Arthur softly cooing in falsetto behind Ernie’s gentle, contemplative lead vocal as delicate flecks of celestial synth pads and keyboards twinkle in the song's night sky; it’s a sensitive, gorgeous swoon somewhat hidden among the record’s meaty rockers and tense new wavers. Then there's "More Real," perhaps Russell's most crystalline attempt at pure, unfettered pop, built upon layers of softly overlapping chords and arpeggiation and anchored by one of Brooks and Chamberlain's most nimble performances on the album. Russell gives what could be his strongest ever vocal performance, utilizing many of his assorted trademark tones, tics, and textures in one single straightforward performance. It's both the single most confident vocal turn and most explicit pop experiment of Russell's career, and Brooks and Tomney's dual backup vocals only add to the song's magic, conjuring endless harmony amidst the somewhat awkward struggles surrounding the album’s creation.

That harmony, sadly, was short-lived, if it had ever truly been there behind the scenes to begin with. The band was never truly happy with the results of the album sessions, feeling both budgetarily shortchanged and crunched for adequate studio time. While Michael Ewing was extremely helpful in guiding the band as closely toward their ambitions as was possible given the constraints, the sessions with Blank were less satisfying. Tomney had hoped to have John Cale produce the album, as he’d been the only producer to successfully capture the band’s live energy in the studio, and could in theory also help the band see their more ambitious studio arrangements come to life. With the miniscule recording budget offered by Sire, though, Tomney felt that after everything that Cale had done for the band in its formative days, he couldn’t bring himself to ask Cale to essentially work for free. And then there was Arthur. While Russell had promised the others upon joining that he'd behave within the defined structures of the group, according to Brooks and Bob Blank, Russell eventually began picking the songs apart in the studio in an attempt to seemingly dismantle their commerciality. While it's obvious that he didn't succeed, listening to the album on headphones reveals multiple layers of both Arthur’s shenanigans and Tomney’s ambitious vision throughout; Michael Ewing subtly tucks quiet call-and-response vocal lines, shimmering droplets of organ and electric piano, and layers of viscous cello and razor-sharp guitar across nearly all of the songs he recorded, making the most of Arthur's failed attempts at sabotage and disorder and using it to Tomney’s advantage. The final product ends up painting a much more vivid picture of Russell's strengths when locked into rigid pop structures than, say, his attempts with the Talking Heads (check the early b-side mix of their "Psycho Killer" that features Arthur's completely ripping cello) or even with the more loosey-goosey structures of the Flying Hearts songs. It's the same reason that Russell's dance singles arguably proved more effective when handed over to outside parties for remixing-- without a steady, controlling hand to pull Russell away from the edge, Arthur often found himself tipping over the cliff, fully submerged in the deep end with no desire to come up for air. The pressures of sticking to a heavily structured, scheduled, and mutually agreed-upon touring and PR regimen as the band approached a commercial breakthrough proved to be too stifling for the shapeshifting Russell, who would often complain about the rigors of road life and rehearsals, which at times conflicted and overlapped with recording sessions and rehearsals for his own numerous projects.

And here is where we address what has become the most widely spread bit of misinformation regarding The Necessaries and Arthur’s tenure with them: the urban legend surrounding his departure. Contrary to popular belief, Russell did not have a panic attack and abandon ship while stuck in traffic at the mouth of the Holland Tunnel, just blocks from the band's rehearsal space and in the eleventh hour before a big headlining gig out of town. While Arthur did indeed step out of the van and walk away, it was because he had misread the Necessaries’ tour itinerary, mistaking a one week multi-city engagement to simply be an overnight show in Washington DC. When he realized that his oversight interfered with recording sessions for a Sleeping Bag Records project that same week, he opted to stay in NYC to fulfill those obligations, apologized to the band, and walked out. The band successfully played those shows as a trio (for the first time since their initial post-Spedding period), and upon returning spoke with Russell, who again apologized and offered to return and commit to the band’s business and obligations. Tomney felt that it was perhaps in everyone’s best interests for Arthur to remain focused and committed to Sleeping Bag’s operations, and with that, Russell amicably parted ways with the band. The Necessaries continued for the rest of that year as a trio, gigging and even recording with Tommy Ramone in the producer’s chair, but sadly disbanded before anything further reached record buyers. Though Tomney, Brooks, and Chamberlain would continue to work with Russell subsequently, it was pretty much the end of Russell's "pop phase" as we humans recognize it. From here on out, Russell almost exclusively devoted himself to the elastic, malleable structures of his own vocabulary, while The Necessaries came full circle and returned to the more ragged and savage fury of their first year.

To ask what could have been will always prove an intriguing question, but what's just as interesting is looking at what did end up happening in the years following The Necessaries dissolution. While it's a stretch to say that the group were big influences on bands like R.E.M., it's worth noting that the two groups did play a number of concerts together before the Athens quartet released their 1982 Chronic Town EP. If anything, though, The Necessaries’ album-and-a-half of Sire material possessed a jangling angularity—a jangularity, if you will—that had more in common with bands just across the river from NYC in Hoboken, New Jersey like The Feelies and The Individuals than anything emerging from Lower Manhattan at the time. Alongside early R.E.M. and Let's Active (who wouldn't actually record until 1983), the Hoboken bands were pretty much the closest thing The Necessaries had to sonic brethren in their Sire era, and while the Feelies hadn't yet fully emerged from hibernation after Crazy Rhythms, which was an altogether more frenetic affair than their subsequent work, they did indeed play gigs with The Necessaries, and listening to the two bands back-to-back reveals more commonalities than perhaps expected. The Necessaries indeed were slightly ahead of the curve in getting a dispatch of that sound’s evolution out there, though both Big Sky and Event Horizon's UK-only micro-releases seemed guaranteed to leave the band to fade into the margins of obscurity, not exactly helping the cause even in terms of archival observation.

After the band’s dissolution, both Brooks and Chamberlain went on to play with NYC singer-songwriter Elliott Murphy for a number of years (though Brooks had actually begun playing with Murphy as early as 1974), and Chamberlain even reunited with Mayo Thompson briefly in 1983 for more concerts and recordings as Red Crayola. He would occasionally record with Russell and Brooks, but drifted from playing music, and sadly passed away in 1999. Brooks also had gigs with former New York Dolls frontman David Johansen for a spell before hooking up with former Beefheart guitarist (and Arthur patron) Gary Lucas throughout the 1990s as a part of his Gods And Monsters band, as well as with composer Rhys Chatham’s large guitar orchestras and former Modern Lovers bandmate Jerry Harrison’s post-Talking Heads band Casual Gods. As of this writing, he is still a member of Gods And Monsters and serves as a member of the band Heroes Of Toolik. He is also responsible for assembling a number of revolving ensembles featuring Arthur Russell’s former collaborators, who continue to perform his songs and longform instrumental works in tribute to their deceased friend and colleague. Tomney, whose pre-Necessaries 1970s ensembles ENVLP and Kerneldack were of a more avant-garde sensibility (think live modular synthesis and Trout Mask and Decals-era Beefheart instrumental clusters), took a more unexpected left turn after playing in a rock band called Rage To Live in the mid-’80s with Individuals frontman Glenn Morrow, who coincidentally co-founded the Bar/None label-- home to the likes of early Yo La Tengo and the Feelies' return to disc, further cementing Tomney's Hoboken connection beyond mere aesthetics. During his stint with Rage To Live, Tomney also liberally returned to electronics again in solo and collaborative projects, coming full circle and eventually leaving the pop/rock landscape altogether in favor of deeper explorations of musique concrète and mechanical noise intoners. He then moved into scoring and soundtrack work for the likes of Roger Corman, Oliver Stone, Tamara Davis, Todd Haynes, and even David Lynch and Mark Frost-- their short-lived 1990 “American Chronicles” documentary series features Tomney’s music. After regular performance in the NYC electronic ensemble Analagos, he retired from public performance and now focuses on scoring work for broadcast media, predominantly in Europe. After his departure from The Necessaries, Arthur Russell would continue to grow more and more elusive, recording a series of songs and singles that betrayed the boundaries of completion before drifting off into the ether himself, but not before somehow managing to release what is perhaps his most definitive statement of unintelligibility: 1986's World Of Echo album.

As the last decade and a half has seen an immense and unexpected renaissance for Russell's music, his tenure with The Necessaries often remained an unfair footnote, and the band has remained a referential non-entity in the overviews of Brooks, Chamberlain, and Tomney, all figures whose talents remained somewhat obscured by time and either a lack of individual discographical heft or the plight of the sideman-- while Brooks and Tomney both have rather slim recorded discographies, Brooks has remained a more peripheral figure due to his lack of true frontman status across the timeline of his career, and even then often known more for his first band than his numerous excellent subsequent projects. Few fans seemed to have even heard of The Necessaries album-and-change worth of material, let alone actually laid hands on copies of any of it. When I met Brooks around 2004 via a mutual friend whose band featured frequent Russell collaborator Peter Zummo on trombone (his horn can also be heard here, on the Event Horizon's lone instrumental "Sahara"), I told Ernie how much I loved the Necessaries records. He seemed shocked that someone so young knew of them, and was tickled to hear that I'd even tracked down a copy of Event Horizon while one of my good friends (also in attendance) had managed to find Big Sky (said friend happens to be Patrick McCarthy, now a producer at Light In The Attic Records). Even at that point, at the start of Arthur's critical revival, Brooks possessed a particular warmth and affection for the material that perhaps only hindsight can nurture among such strained circumstances. He and Tomney remain wholly proud of their time together in this band, though Event Horizon proved perhaps too accurate a title for this album, a point of no return for a band standing at the precipice of their combined powers, not just once but four times over-- a quartet of the city's finest undersung rock talents who managed to give us some of the most confident performances by one of downtown NYC's most notoriously elusive troublemakers before plummeting off that precarious edge into the abyss. While the group was perhaps "too niche for its own good" back in 1982, looking at The Necessaries' output in 2017 shows a band whose disappearance allowed for others to slowly but surely catch up and provide the context that was Necessary all along. Here we are, coming back because our love is more real. What happens next is up to us, dear readers. There’s more of this story to be told… make sure that they know you’re listening.

Michael IQ Jones, August 2017