Steve Hiett

Down On The Road By The Beach

Original Release: Sony Music Japan 1983

Reissue: Be With Records / Efficient Space 2019

Liner Notes: Michael IQ Jones

Photography: Steve Hiett

"What is blue? Blue is the invisible becoming visible... Blue has no dimensions. It 'is' beyond the dimensions of which other colors partake."

In 1957, French conceptual artist Yves Klein quietly declared this statement to a page in his personal journal, and would spend much of his subsequent career expanding and refining his answer into tangible variations on an absolute manifestation. While giving a guest lecture at la Sorbonne in Paris on June 3rd, 1959, he expanded upon this musing:

"Blue has no dimensions, it is beyond dimensions, whereas the other colors are not. They are psychological spaces; red, for example, presupposing a hearth releasing heat. All colors bring forth specific associative ideas, tangible or psychological, while blue suggests, at most, the sea and sky, and they, after all, are in actual nature what is most abstract."

Blue exists in our world as both a pigment and a psychological concept, an emotion, a feeling which consumes and at times even overwhelms, and which has led to the creation of many of modern culture's most beloved artifacts across a number of media. Historical awareness of the existence of blue only goes back so far as the early Mesopotamian empire, when lapis lazuli, a mineral imported from a fabled and near-impenetrable mine in northeastern Afghanistan, was used as a decorative gemstone in sculpture and headdress. The ancient Egyptians, who prized lapis for its rarity and vibrancy of hue, around this time also created the world's first blue pigment dye and paint out of limestone and azurite, and for the first time humans could not only visualize blue in the world, but also conceptualize the color as something greater than an aesthetic. Lapis lazuli became known as "ultramarine," derived from the Latin ultramarinus: "beyond the sea," and with this ambitious rebranding, blue became a color predominantly associated with luxury and rarity, reserved for only the finest artistic commissions or tributes to royalty. With the passage of time, craftspeople and artisans across the globe began making use of minerals and plants to develop their own distinct shades of the color, and with that expansion of the spectrum of blues, our expression of the color's emotional register simultaneously evolved with increasing depth.

The album you currently hold in your hands is arguably the most quintessential synchronous representation of blue(s) in its myriad forms: visual, emotional, musical, ephemeral, valuable. Its creator, a humble Englishman, quietly released it into the world in 1983 solely in Japan which, in a pre-internet world, was the Western musical equivalent of hiding a treasure in the Sar-i Sang lapis lazuli mine in hopes that it would one day be excavated and prized in new contexts. That time is now, and that creator is Steve Hiett---an esteemed artist who, alongside Yves Klein, is arguably as equally deserving of his own distinct signature blue hue. (Attention Pantone: can we make this happen, please?) The story of his lone album and the journey it has taken to reach its current rapturous, cult-like adoration and fetishization over thirty years after its creation is a tale of many tangents and degrees of separation, each tied together via Hiett's portfolio as a visual artist.

Born in 1940, Hiett is most widely recognized in the art sphere as a photographer and graphic designer, and his pioneering technical and aesthetic language—at once deeply personal and yet universally understood—are now so commonplace in contemporary culture and industry that his influence is easily (and unfortunately) taken for granted. He was one of the first modern photographers to fully explore and exploit the usage of flash in outdoor daylight--now a commonplace technique in fashion photography--and his prints show an arresting understanding of color and tone. Unlike an amateur abusing loud volumes of color oversaturation to drown out an average or middling composition, Hiett's eye sees beauty and magic in the minutia of urbanity's mundanity, magnifying simple details of suburban architecture. His first book, 1976's Pleasure Places features, in Steve's words, "simple pictures of quiet, empty places" that nod backward at his humble roots while following a road down his artistic future where the majority of his photographs would be set. Steve's humble synopsis of Pleasure Places sets us back at the beginning of his tale (and will later go on to connect us right back to this album), so let's flashback:

"When I left art school I joined a band. I just decided that's what I would rather do, and on quiet Sundays I used to go for walks around Bromley, where I was living. I like empty suburban streets. No one around, beautiful gates and quiet gardens."

That band was called The Pyramid, and as Hiett tells it, "I was studying at the Royal College of Art when my friend Dave Chastain called me one night because he knew this band called The Pretty Things, and he says, 'the guitar player is sick... could you come and play guitar [with them]?' So literally thrown into the deep end, I started playing with The Pretty Things! After that [gig], I was waiting at the bus stop to go home and thought, well, I'd probably prefer this to doing graphics!" He quickly formed a band at the Royal College called Colours, who had secured a gig at a club called Brazz in London's Soho district playing cover tunes from 10pm until around 5am nightly. Their manager, in Steve's words a "very rich kid from the Royal College's industrial design department," had hopes of joining Colours as saxophonist, but while Steve had no need for a horn, his funds were a different story. Having a different concept for the band, their manager scrapped everyone save for Hiett and Albert Jackson, recruited Iain Matthews--later of Fairport Convention and Matthews' Southern Comfort--and thus The Pyramid was built.

Their lone 45, "Summer Of Last Year," was released in 1966 on Decca Records offshoot Deram, features the session talents of heavyweights like Big Jim Sullivan, John McLaughlin, and John Paul Jones (yes, later of Led Zeppelin), and wears Steve's love for the Beach Boys proudly on its sleeve and in its harmonies. It was also Hiett's first foray into published songwriting. The A-side blends a psychedelic mod groove with rich, intricate vocal harmonies heavily indebted to the Wilson family. Beach Boys mastermind Brian Wilson would also heavily influence the structure of the single's music as well:

"At that point I was really into the Beach Boys chord progressions because they were so complex. Then I just started writing stuff that was basically, well I thought was like Jack Kerouac beat poetry lyrics over Beach Boys chord progressions, that’s how I saw it in my head. "The Summer of Last Year" was basically Beach Boys influenced with major 7ths and minor 7ths. That sort of stuff that just didn’t exist - I learnt them from Beach Boys records. On the b-side, "Summer Evening," I was really getting in gear with my trippy beat poetry - 'over there against the trees, the girl in her bleak dress' - in a way that was a prototype for some fashion pictures I was going to do. At that point, in the late 60s, The Beach Boys were considered to be the lowest of the low. They were considered to be a nerdy band that no one was interested in but I loved all their early stuff before Pet Sounds. I was known around London scene as this guy Steve Hiett who liked The Beach Boys."

Wilson would infiltrate Steve's early photography jobs as well, in more ways than one: Hiett was one of the first people to ever photograph Jimi Hendrix, and that invitation to the Isle Of Wight Festival in 1970 came about thanks to an earlier gig shooting the Beach Boys in Birmingham for Rolling Stone via their UK editor Andrew Bailey. By this point, The Pyramid had disbanded after failed attempts to work with producer Tony Visconti, and Steve had shifted his artistic focus into the world of fashion photography, again almost accidentally:

"The Pyramid decided to call it a day and after that all I knew for certain was that I just didn't want a 9-to-5 job. One day I was walking down Frith Street in Soho when I saw a friend from the Royal College; when I told him what had happened he simply said, 'Why don't you try fashion photography?' I had just that morning been thinking about maybe trying that, so his words just clinched it."

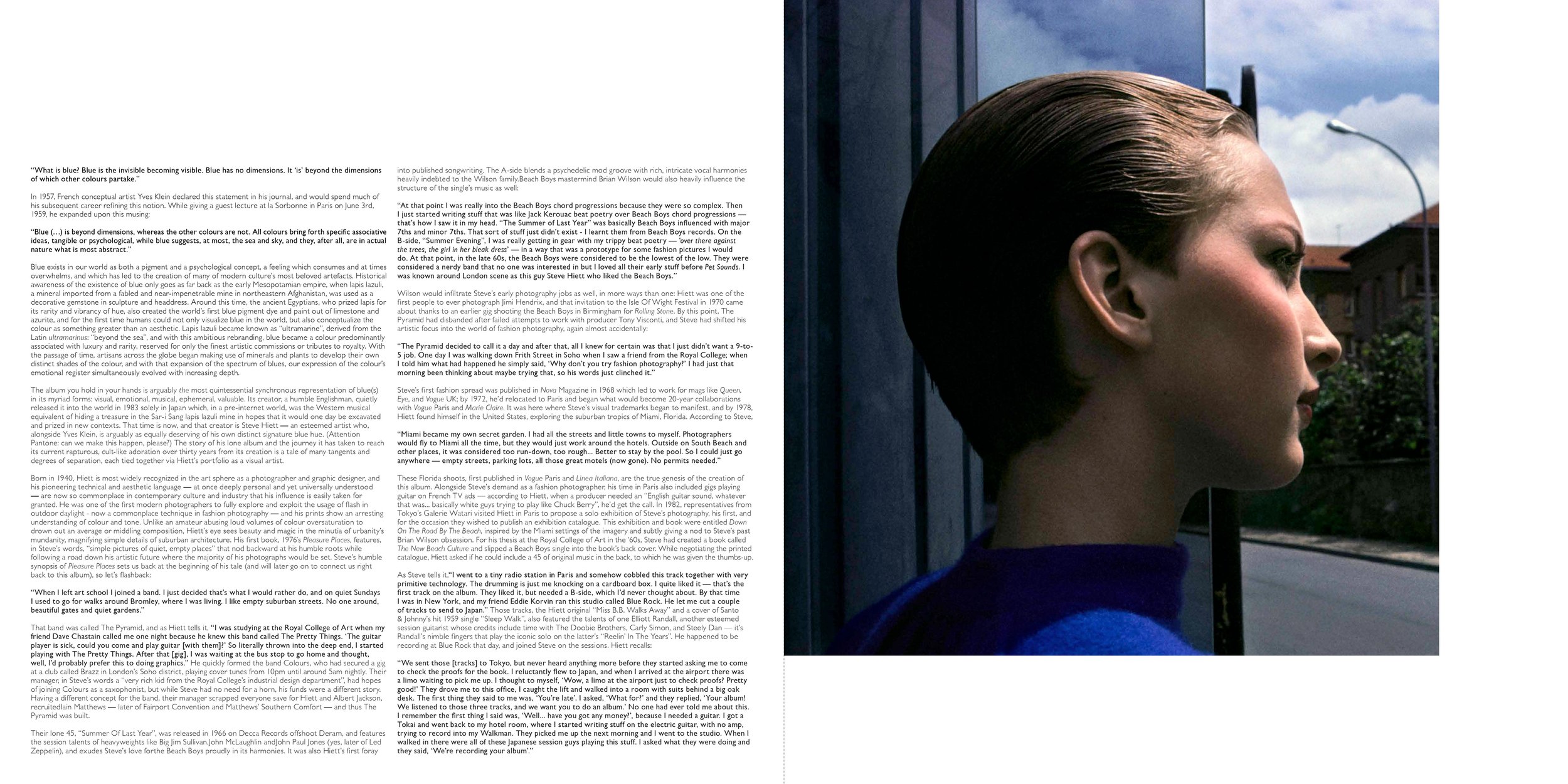

Steve's first fashion spread was published in Nova Magazine in 1968 which led to work for mags like Queen, Eye, and Vogue UK; by 1972, he'd relocated to Paris and began what would become 20-year collaborations with Vogue Paris and Marie Claire. It was here where Steve's visual trademarks began to manifest, and by 1978, Hiett found himself in the United States, exploring the suburban tropics of Miami, Florida. According to Steve, "Miami became my own secret garden. I had all the streets and little towns to myself. Photographers would fly to Miami all the time, but they would just work around the hotels. Outside on South Beach and other places, it was considered too run-down, too rough... Better to stay by the pool. So I could just go anywhere -- empty streets, parking lots, all those great motels (now gone). No permits needed."

These Florida shoots, first published in Vogue Paris and Linea Italiana, are essentially the true genesis of the creation of this album. Alongside Steve's demand as a fashion photographer, his time in Paris also included gigs playing guitar on French TV adverts--according to Hiett, when a producer needed an "English guitar sound, whatever that was... basically white guys trying to play like Chuck Berry!," he'd get the call. In 1982, representatives from Tokyo's Galerie Watari visited Hiett in Paris to propose a solo exhibition of Steve's photography, his first, and for the occasion they wished to publish an exhibition catalogue via CBS/Sony. This exhibition and book were entitled Down On The Road By The Beach, inspired by the Miami settings of the imagery and subtly giving a nod to Steve's past Brian Wilson obsession. For his thesis project at the Royal College of Art back in the '60s, Steve had created a book called The New Beach Culture and slipped a Beach Boys single into the book's back cover. While negotiating with the suits at CBS/Sony about the Down On The Road book, Hiett asked if he could include a 45 of original music in the back, to which he was given the thumbs-up.

As Steve tells it, "I went to a tiny radio station in Paris and somehow cobbled this track together with very primitive technology. The drumming is just me knocking on a cardboard box. I quite liked it - that’s the first track on the album. They liked it, but needed a B-side, which I’d never thought about. By that time I was in New York, and my friend Eddie Korvin ran this studio called Blue Rock. He let me cut a couple of tracks to send to Japan." Those tracks, Hiett original "Miss B.B. Walks Away" and a cover of Santo & Johnny's hit 1959 single "Sleep Walk," also featured the talents of one Elliott Randall, another esteemed session guitarist whose credits include time with The Doobie Brothers, Carly Simon, and Steely Dan--Randall's nimble fingers are playing the iconic solo on the latter's "Reelin' In The Years." He happened to be recording at Blue Rock that day, and joined Steve on the sessions. Hiett recalls:

"We sent those [tracks] to Tokyo, but never heard anything more before they started asking me to come to check the proofs for the book. I reluctantly flew to Japan, and when I arrived at the airport there was a limo waiting to pick me up. I thought to myself, 'Wow, a limo at the airport just to check proofs? Pretty good!' They drove me to this office. I caught the lift and walked into a room with suits behind a big oak desk. The first thing they said to me was, 'You’re late.' I asked, 'What for?' and they said, 'Your album! We listened to those three tracks, and we want you to do an album.' No one had ever told me about this. I remember the first thing I said was, 'Well... have you got any money?,' because I needed a guitar. I got a Tokai and went back to my hotel room, where I started writing stuff on the electric guitar, with no amp, trying to record into my Walkman. They picked me up the next morning and I went to the studio. When I walked in there were all of these Japanese session guys playing this stuff. I asked what they were doing and they said, 'We’re recording your album.'"

Those Japanese session guys, unbeknownst to Steve, happened to be none other than Moonriders, one of Japan's most successful and acclaimed rock bands of the 1980s. "That was because the producer... I don’t know if he’d made some sort of deal with [Moonriders], but I was told I had to do a track with them. I wrote something which they improvised over. That was part of the deal. They were very nice guys, so I was happy to do it. On "By The Pool," there’s a guy from that band on violin. He played a beautiful part on it."

Their collaboration, unfortunately, did not get off to a most successful start. As Steve recalls, "They sat me down on a chair, but I kept missing my cue. I was so jet lagged and it was very complex stuff that I couldn’t figure out at all. They gave me sheet music and I said, 'I can’t read a note of it.' So that was a disastrous start and I just said to them, 'Tomorrow I just want to do a single track, just acoustic, I won’t need you guys, I’ll call you when I need you.' It turned out to be a good thing, because they left all of their equipment in the studio, so I had drums, bass, guitars, effects pedals, everything. It was all just there, so I never called them. That's how I put the album together."

The one song most illustrative of the sessions' complicated start is "Hot Afternoon," credited to Moonriders keyboardist Toru Okada and featuring the full band attempting to magnify the aesthetic of Hiett's earlier solo and duo cuts into a bright, beaming personification of high noon, while Steve provides percussive, onomatopoeic layers of multitracked harmony vocals. Elsewhere on the album, Moonriders' contributions are sporadic and considerably more minimal--a violin here, a third guitar there, the occasional splash of keyboards throughout. But thankfully, Steve was able to convince the suits at Sony to fly Elliott Randall back in for the sessions at Shinanomachi Studio, and he found some comfort in having a creative foil with whom he could more easily communicate and craft the album's vibe. "At some point I said, 'Wouldn’t it be nice if we get Elliott Randall to come along as well?' In those days money was no object. When I called him up in New York, he cancelled all of his sessions and turned up the next day. And then we finished the album together."

Though New York, Paris, and Tokyo aren't really known for their beaches, Hiett's knack for so beautifully illustrating the mood and the elemental feeling of the beach for this album reaches back to those days at the Royal College. The B-side of that lone Pyramid single, "Summer Evening," is the single's real highlight, and lays out the aesthetic musical blueprint of Down On The Road's entire seascape in lush, vivid Kodachrome. Its spindly, serpentine guitar, softly droning organ, and gentle percolations of percussion anchor lush vocal harmonies and offer a glimpse at the sorts of things Steve could've been exploring more deeply had he not decided to abandon bandleading for years following an unfortunate Pyramid gig that left him with a spinal fracture via electrocution. Regardless of however long it took to get him back in a studio, though, one thing is clear: as stated earlier, Down On The Road By The Beach is the quintessential manifestation of blue in its many forms.

Its sleeve features a striking image of model Juliette Desurmont taken by Hiett during a 1979 shoot for Elle France, her face fully obscured by a long shadowy line that darts across the landscape of her body as she stands, almost paralyzed, by the blazing sun of a hot afternoon. Behind her is the eponymous road and beach, but further behind them are the sea and the sky, so dark in their vast abysmal mystery, so powerfully present and yet innocently, quietly, simply existing. This is true of the album's music as well, a mix of Hiett originals, the aforementioned Okada piece, an atmospheric closer penned by Japanese icon Kazuhiko Kato (of the Folk Crusaders and the Sadistic Mika Band), and a quartet of cover songs chosen by Steve which further illustrate Hiett's mastery of blue subversion.

We've already spoken of Santo & Johnny's "Sleep Walk." Eddie Floyd's 1967 soul hit "Never Found A Girl" was first heard by Steve after flying to New York to record at Blue Rock Studio, and is recast here as a shy blues shuffle, its original string arrangement and head-bobbing rhythm replaced entirely by layers of intertwined guitars and a snap-clap beat, with Hiett's rare lead vocal turn---one of just three, all found on the album's first side---swapping Floyd's robust tones with a humble everyman's amorous declarations, bearing striking similarity to those of The Durutti Column's Vini Reilly. In fact, from an aesthetic perspective, Reilly's work (itself in its infancy with just a handful of releases by Down On The Road's 1983 release) is one of Hiett's only true (albeit coincidental) kindred spirits of the era, though Vini's own explorations of blues and soul styles were still years away.

A loose cover of Chuck Berry's "Roll Over Beethoven" recasts the rollicking original into a tune more casual than a pair of linen shorts, with Steve's vocal nearly evaporating into the atmospheric heat as overlapping slide guitar lines ping-pong across the stereo field. Hiett's cover was, according to Steve, "Just a bit of a laugh, recorded while I was waiting for Elliott to come from the airport. I think I was playing it through a phaser or something. It was much much longer with a lot of guitar stuff on it, but the guy who produced it cut it down [in the final mix]." A laugh or otherwise, it's emblematic of how successfully the record takes Steve's love of the blues as a musical artform and recasts it in a personal light. Rather than the overt fetishistic copyisms of many white musicians' attempts to embrace the blues, Hiett speaks it in his own aesthetic language, the same one that makes his photography so vivid and sumptuous and enigmatic. To quote the great Ralph Ellison:

"The blues is an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one's aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy, but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism. As a form, the blues is an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically." -Richard Wright's Blues, Summer 1945

And while Hiett's take on the old Cliff Richard & The Shadows cut "The Last Time"---recast here as an instrumental by Steve because "I just love that melody"---offers a fine example of injecting blues undertones into a song originally performed by a crooner who'd never be mistaken as a bluesman, perhaps nowhere else on this album is Steve's mastery of recontextualization better demonstrated than on original tune "By The Pool." Arguably the album's highlight and most highly praised/canonized cut, "Pool" is a zero-gravity blues, a memory of pain and anguish bleached away by southern sunlight until all that remains is the longing tenderness of a misguided nostalgia for failed love and the soft sob of a splash of water. Steve has spoken of his preference for pre-Pet Sounds Beach Boys---"I always loved that mid-period Beach Boys - things like "She Knows Me Too Well," "The Girls On The Beach," "Don’t Worry Baby." Just before Pet Sounds when he was doing these incredible chord progressions with rich vocal harmonies. To me that just sounded like this beautiful hot summer sound"---but "By The Pool" is Hiett's own "Don't Talk (Put Your Head On My Shoulder)": sophisticated, minimal, powerful, beautiful.

In this one song, we experience the emotional core of the record: the beach, the sun, the peace of the environs underlaid by the melancholic turbulence of the crashing of surf... simultaneously one with the magnificent splendor of the natural world, the forlorn intimacy of loneliness, and the overwhelming calm we feel when we experience them. It is the beach as described by someone who has only ever been told of it rather than swam in it: not an outsider, but someone so far away that they conjure it into their existence.

Down On The Road By The Beach, originally meant to be an audio soundtrack to the photo book and exhibition of the same name, but mysteriously never included with it, was only ever initially released in Japan on LP and a very miniscule cassette edition which is even rarer than the original vinyl pressings. It trades among crate diggers and enthusiasts for large collector sums largely thanks to the word-of-mouth of modern internet media, frequently appearing amidst autoplay algorithms and mixtapes curated by contemporary connoisseurs. As Steve describes it, its genesis was entirely accidental, an oasis of introspection and modernized nostalgia crafted in makeshift environments and workspaces, meant to serve a specific purpose, but whose release was curiously entirely removed from such. But the LP's dreamy, weightless, near-ambient arrangements belie the emotional heaviness it conjures in contemporary listeners, myself included. It has become a holy grail or desert island disc, one of those albums you grab should the house catch fire. The album's recent global renaissance baffles Hiett, but delightfully so.

"I don’t even know where they’ve been hearing it, but I’m very happy about it. It's funny because it's something that was done so casually. The first track recorded in a radio station in Paris, those two demos in New York with Elliott Randall. Then I turned up in Japan [and] thought I was there to check proofs... suddenly I had to record an album, going back to my hotel room every night to come up with another tune. That’s how it all came about!"

Hiett's relationship with Japan and the balearic underground also extends beyond this album, as his photos have graced the sleeves of a number of Japanese albums during the era, most notably among them the Hiroshi Sato/Wendy Matthews ambient synth-pop masterpiece Awakening, whose sleeve is decorated by one of the quiet snaps first published in the Pleasure Places book. When describing his photographic work of the 1980s, in his opinion "his best period," Hiett recalls, "Things got simple: a Contax 35mm, one Norman flash, one Polaroid 180 camera, and one 35mm lens. For everything. This meant I could travel light and keep things as simple as possible. Work fast, anywhere, anytime, any light." One can't help but feel that his experience recording this album helped to contribute to that efficiency of inspired creation. For something done "so casually," it sparked an obsession with the blues in its creator, who'd continue throughout the 1980s to photograph, make TV adverts, music videos, and pen the occasional pop tune in Paris. He claims that no matter where he'd be shooting, though, he'd always bring his guitar, and throughout the '80s he continued quietly recording tracks privately with his friend Simon Kentish. Around this time, he would also begin a thematic series of photos that moved away from the beach, finding new Pleasure Places in lush green spaces. That's a story to be told in another liner note.

Michael IQ Jones, May 2019