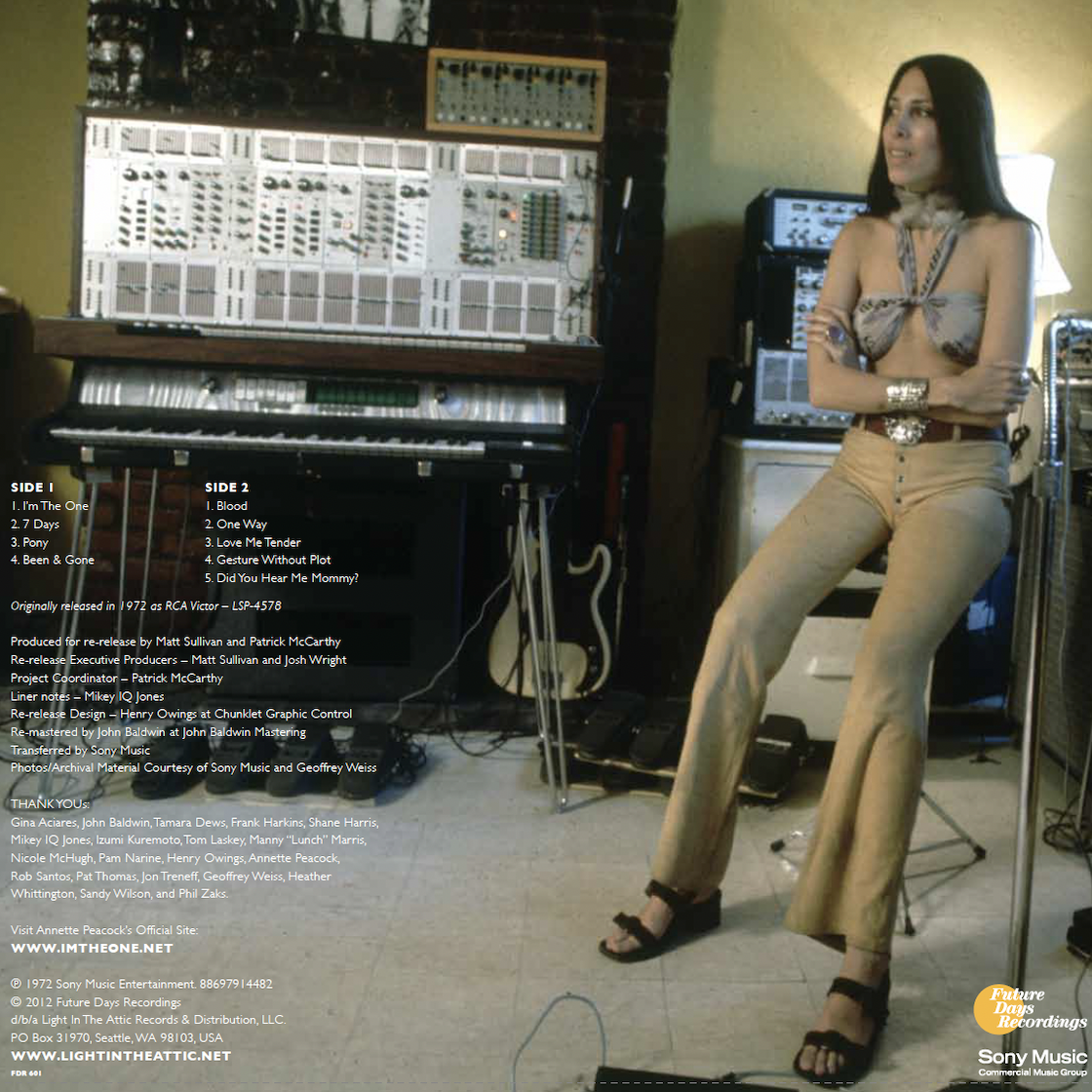

Annette Peacock

I’m The One

Original release: RCA Victor 1972

Reissue: Light In The Attic 2012

Liner Notes: Michael IQ Jones

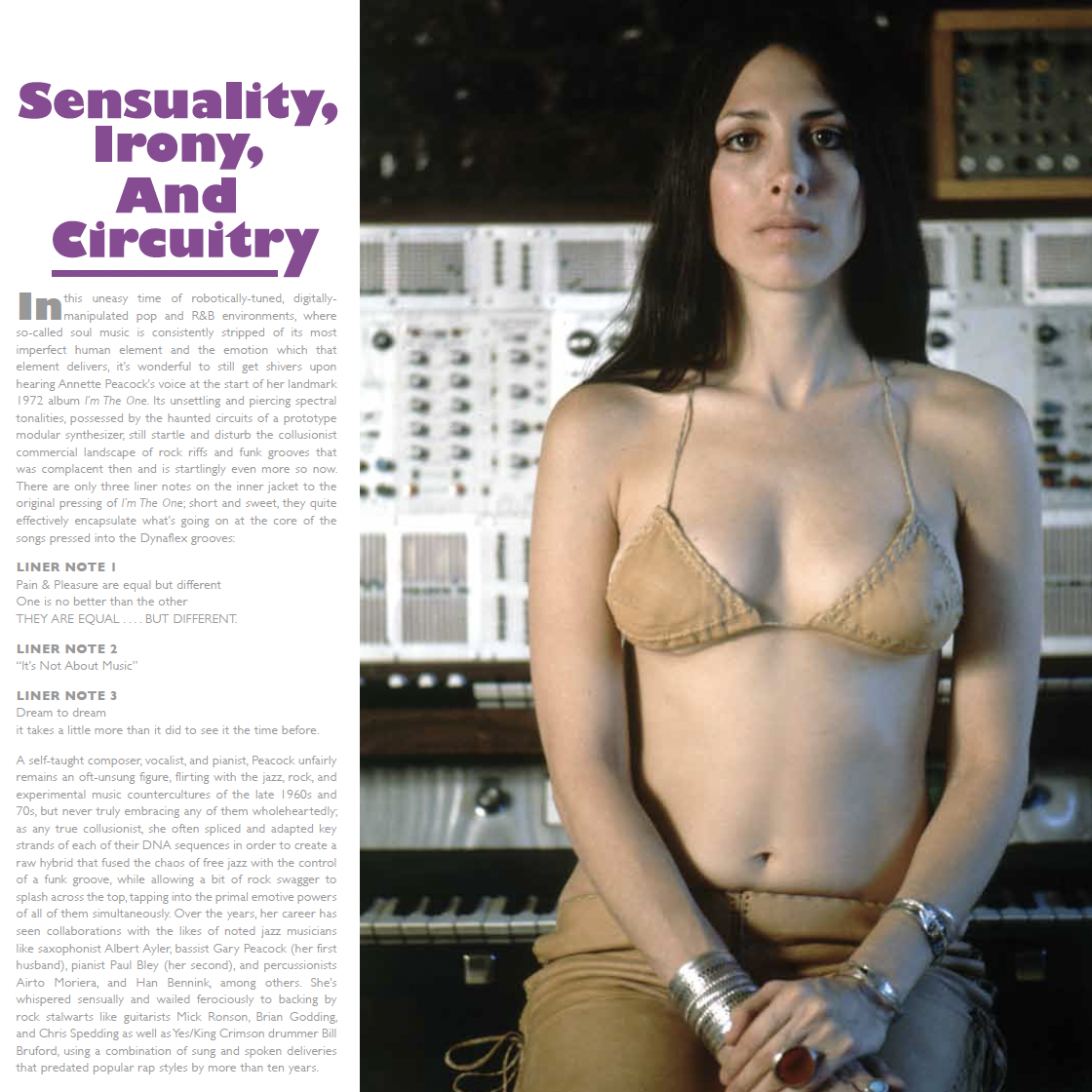

In this uneasy time of robotically-tuned, digitally-manipulated pop and R&B environments, where so-called soul music is consistently stripped of its most imperfect human element and the emotion which that element delivers, it’s wonderful to still get shivers upon hearing Annette Peacock’s voice at the start of her landmark 1972 album I’m The One. Its unsettling and piercing spectral tonalities, possessed by the haunted circuits of a prototype modular synthesizer, still startle and disturb the collusionist commercial landscape of rock riffs and funk grooves that was complacent then and is startlingly even more so now. There are only three liner notes on the inner jacket to the original pressing of I’m The One; short and sweet, they quite effectively encapsulate what’s going on at the core of the songs pressed into the Dynaflex grooves:

LINER NOTE 1

Pain & Pleasure are equal but different

One is no better than the other

THEY ARE EQUAL . . . . BUT DIFFERENT.

LINER NOTE 2

“It’s Not About Music”

LINER NOTE 3

Dream to dream

it takes a little more than it did to see it the time before.

A self-taught composer, vocalist, and pianist, Peacock unfairly remains an oft-unsung figure, flirting with the jazz, rock, and experimental music countercultures of the late 1960s and ‘70s, but never truly embracing any of them wholeheartedly; as any true collusionist, she often spliced and adapted key strands of each of their DNA sequences in order to create a raw hybrid that fused the chaos of free jazz with the control of a funk groove, while allowing a bit of rock swagger to splash across the top, tapping into the primal emotive powers of all of them simultaneously. Over the years, her career has seen collaborations with the likes of noted jazz musicians like saxophonist Albert Ayler, bassist Gary Peacock (her first husband), pianist Paul Bley (her second), and percussionists Airto Moriera and Han Bennink, among others. She’s whispered sensually and wailed ferociously to backing by rock stalwarts like guitarists Mick Ronson, Brian Godding, and Chris Spedding as well as Yes/King Crimson drummer Bill Bruford, using a combination of sung and spoken deliveries that predated popular rap styles by more than ten years.

It was a meeting with inventor Robert Moog, though, who gave Annette and Paul a prototype model of his modular Moog Synthesizer, that was the key which opened the door to Annette’s most wild innovation: the use of analogue synthesis to embellish, manipulate, and at times even fully mutate the human vocal range into otherwise unattainable frequencies, most often in a live performance setting. There were few people in the late 1960s pursuing the sounds of synthesized or electronically-manipulated music outside of the classical or experimental/research mediums, and next to none of them were women; even Switched-On Bach, the album which effectively broke the synthesizer into a more widespread, mainstream listening culture, was created by a man at the time — upon the album’s initial release, Wendy Carlos was still known legally as Walter. Records by the likes of California group the United States Of America, who eschewed the de rigeur fuzzed-out electric guitar in favor of extensive ring modulation to augment the sounds of their electric bass, violin, keyboards, and even drums, or England’s pioneering collective The White Noise, whose An Electric Storm utilized the ingenuity of pioneers from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop to fuse psychedelia with musique concrète, both maximized their psychedelic impact via avant-garde techniques, yet neither were working with the synthesizer as we know it. New York’s Silver Apples made two incredible albums of hypnotic psych-beat music using only a massive drum kit and a homemade primitive synthesizer constructed from banks of oscillators and frequency modulators controlled by switches and foot pedals.

One of the only female contemporaries Annette had in that regard (aside from BBC Radiophonic Workshop member Delia Derbyshire, a brilliant composer who worked almost solely with recorded tape as a source medium) was Ruth White, another American composer best known for two classic albums of experimental Moog soundscapes released on the Limelight label; while 1968’s Seven Trumps From The Tarot Card And Pinions was an entirely instrumental affair, its 1969 follow-up Flowers Of Evil saw White reciting English language translations of many works by French poet Charles Baudelaire, all set to menacing, evocative soundscapes created by the Moog. While her voice was indeed treated with effects throughout, she mainly haunts an echo chamber, leaving the Moog to textures created without the input of White’s vocal cords.

Annette’s work was the exact opposite. Peacock was fond of using the Moog to manipulate only vocal inputs with extraordinary results, work which began with the Bley-Peacock Synthesizer Show’s landmark Revenge album, recorded in 1968 but not released until 1971. On the album’s back cover is a small but sage note warning the world of the chaos to come:

Vocal treatment through the synthesizer is a natural and organic evolution. It is also an innovation to the recording industry. This album is not only important historically, as it marks the beginning of a new era in vocal and instrumental “treatments”; it also marks the beginning of a new and important musical career, that of Annette Peacock whose influence we are convinced will be varied and widespread.

Revenge set the wheels rolling, with a more loose blueprint of the sound which emerged fully matured on I’m The One; she conjures her monologues through an analogue Ouija while backed by Paul Bley and a cast of jazz groovers who anchor her arrangements with lithe, slinky grooves as she sends her voice, synthesized live in the studio often in one take, as far into the stratosphere as it can reach. The folks at RCA caught wind of Revenge, released on Polydor, and quickly signed Annette at the same time David Bowie and Lou Reed scored deals with the label, allegedly in an effort to gain some much-needed industry cool points. Annette recorded I’m The One for the label in late 1971, opening the album with newly recorded versions of Revenge’s “Climbing Aspirations” and “I’m The One,” here fused into one piece bearing the latter’s name.

What follows is twenty-five minutes of aching torch song, razor-sharp barbed wire funk, and some dark, droning moodscapes that echo Ruth White’s work on Flowers Of Evil. Annette weaves a dark braid of Tin Pan Alley blues stylings throughout many of the songs, with the spare “Seven Days” and “Been And Gone” re-sculpting Nilsson-esque piano ballads into more ethereal tone poems, while “Pony”’s slinky funk fuses one of Annette’s earliest monologues about sexual satisfaction—a topic she’d revisit in much greater detail on 1979’s excellent The Perfect Release—to some of her wildest, most dense latticeworks of electronic exhalations. Imagine Tim Buckley’s Starsailor and Greetings From L.A. albums fused into one work, or a freak-funk fantasy where Miles Davis circa Get Up With It backs up his Betty on her femme-funk classic They Say I’m Different.

“One Way” opens with what sounds like a voudou ceremony, all clattering percussion (courtesy Airto, Dom Um Romao, and Barry Altschul, each heavyweights in their own right) and droning chords, as she intones lyrics like “I tried to know you... I tried to love you... I wanted to help you grow, let you know... Just help me be someone!” A minute and a half in, a mournful brass fanfare carries her blues as a horror film organ rises like Dr John as the Phantom Of The Opera from the left channel. “Why can’t you love me the way that I love you!?” Her man’s still not getting the picture, apparently, because the album’s sole cover tune follows, a version of “Love Me Tender” that pulsates slowly on a quiet storm nod, as she shows her lover how tenderness is done. The sparse coda of the penultimate “Gesture Without Plot” points toward the experimental quietude she’d further explore via her own Ironic Records release I Have No Feelings in 1986, made in collaboration with UK improviser and experimental percussionist Roger Turner. The album closes with a brief piece recorded with her young daughter Apache Bley, “Did You Hear Me, Mommy?” As young Bley improvises on the piano, sparse notes are slowly surrounded by a swirling cloud of bells and what could be the clatter of kitchenware as Annette sets the table for dinner, until we’re greeted by an eager young voice:

“Okay, that was really nice, Mom, but did you hear me? Did you hear me, Mommy?”

One thing is certain: Bowie certainly heard the album. After Annette kicked him out of the studio during recording, having a strict session-players only policy to maximize efficiency, Bowie requested a copy of the album from RCA and quickly played it to anyone who’d listen, including his manager Tony DeFries, who would subsequently sign Annette to his MainMan management company, who oversaw Bowie at the time, as well as Iggy Pop, Dana Gillespie, and guitarist Mick Ronson. Ronson also happened to be in the studio with Bowie that fateful day, and he showed his enthusiasm and gratitude to Annette by covering two originals from I’m The One AND using her arrangement of “Love Me Tender” on his 1974 solo album Slaughter On 10th Avenue and its followup single, “Billy Porter.” Bowie in turn asked Annette to play on his Aladdin Sane album, and though she refused, keyboardist Michael Garson, who left his distinct mark on Annette’s record, said yes. Bowie then asked Annette to let him produce her next record; instead, she went to Juilliard.

Annette’s next album wouldn’t be released until 1978, six years after I’m The One. X-Dreams featured both new material, as well as songs cut in 1971 and ‘74. Regardless, the album offered a fluid evolution of Annette’s sound, but with one key element missing: the vocal synthesis. From here on out, her voice would be out in the wilderness, naked and alone, tender yet tough, simultaneously urban and urbane. In 1999, Bowie still had Annette on his mind; the coda of his “Something In The Air” from Hours... cribs the chord sequence of the similarly structured “I’m The One” and even winks at its blueprint via the use of ring-modulated vocals throughout.

As for Annette, she records sporadically, releasing an album every five to ten years, usually via her own label Ironic, which she established in the 1980s after being jerked around by an industry who had yet to catch up to her. She remains a passionate advocate, an enigma caught between the peace and love vibrations of a hippy counterculture and the more worldly intelligence of the modern age. Her records continue to influence and inspire, and with I’m The One finally back on the shelves, countless new jacks on the scene can scope its liner notes and bear witness to its brilliance:

All the electronic sounds you hear were generated by the voice of and created by Annette Peacock.

There are a scarce few contemporary performers and composers about which you could make similar claims. To quote Annette in “Gesture Without Plot”:

Here I am dreaming by myself

Captured by a point in time

Visioned by prisms in my eyes

& I seem to wonder what went wrong

I had a dream it didn’t last too long

And the voices keep saying

Did you know that it’s all changing

Fly, and the goat keeps eating caring not at all

The fear is that you might fall.

It’s time to lean in and take the plunge.

Michael IQ Jones, 2011